Your CNC drawing may look fully compliant, yet suppliers still reject it due to “tolerance stack-up risk.” These rejections usually appear after long quoting delays, right when your schedule can’t afford surprises.

CNC tolerance stack-ups get rejected when the required fixture stability, post-process growth control, or inspection access exceeds a supplier’s capability — even if design tolerances are correct. Prevent this by verifying tolerance-chain control before requesting quotes.

Now let’s break down which stack-ups trigger instant supplier no-quotes, how to spot them early, and how to confirm a shop can hold your full chain without redesign or timeline risk.

Table of Contents

Which CNC tolerance stack-ups will trigger a supplier no-quote?

Suppliers no-quote CNC tolerance stack-ups when the chain demands multi-operation accuracy, controlled post-finish shifts, or inspection access they cannot guarantee. The risk isn’t your design — it’s their inability to control datums and verify during the process.

Common triggers engineers see:

- Datums broken during re-clamps late in the sequence

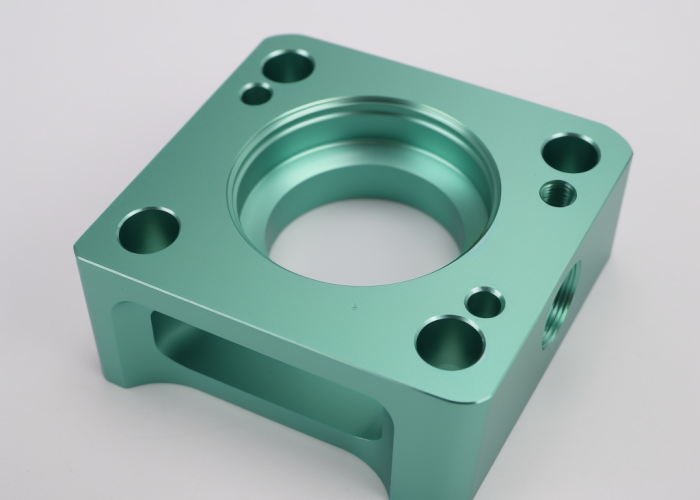

- Thin walls drifting during finishing or anodizing

- 0.01 mm runout that spans three+ ops

- Long features where fixture repeatability collapses

- Functional surfaces not measurable until final QC

Shops avoid quoting when they can’t ensure an operation-to-operation feedback loop. They don’t want risk sitting on their side of the table.

What to do before quoting

Ask this single question:

“How do you plan to maintain and re-confirm my primary datum across all operations?”

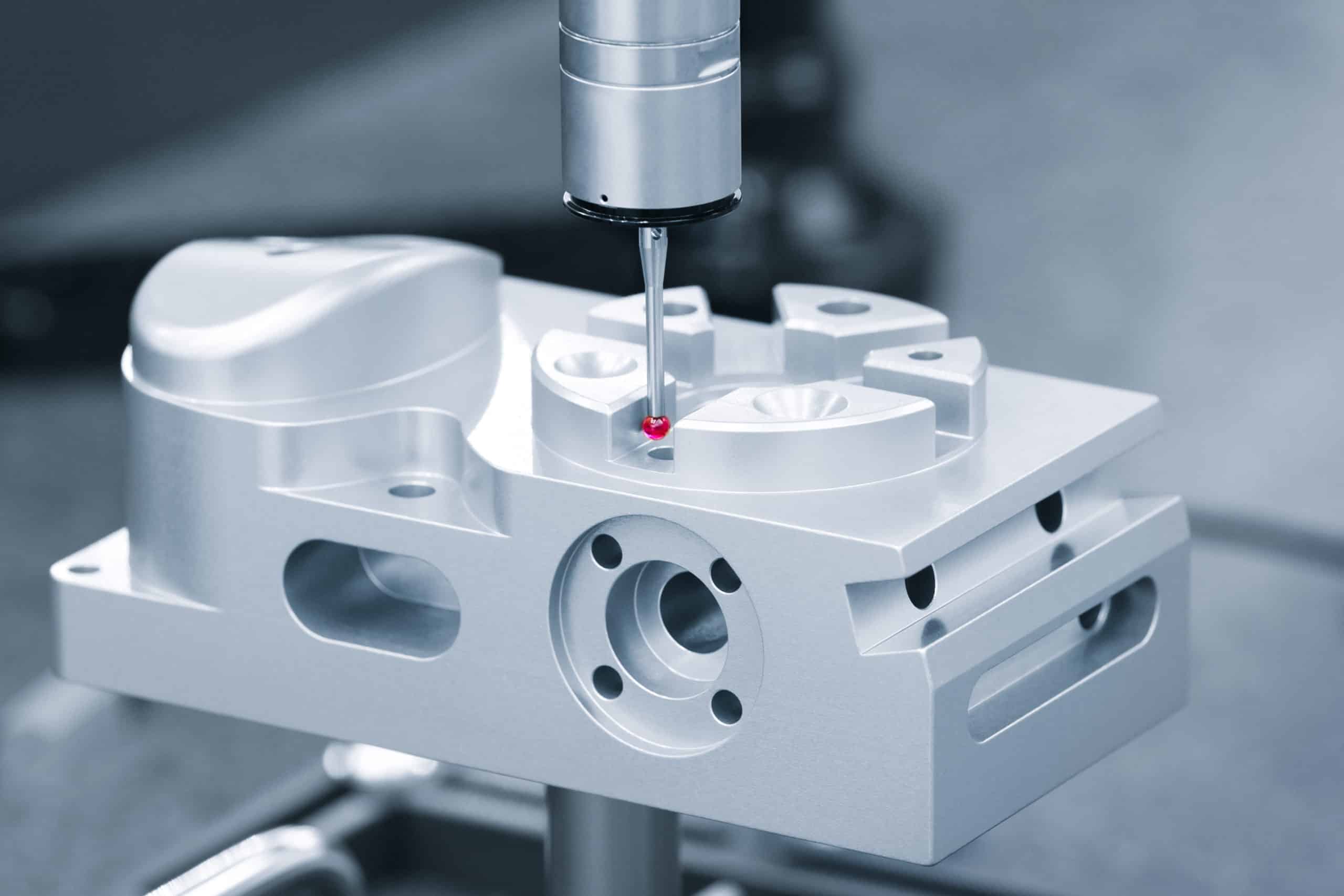

If the answer is basically “final CMM check,” expect delays, scope changes, or a no-quote. A tolerance loop review before RFQ prevents wasted weeks.

What CNC feature combinations cause tolerance chain conflicts?

Tolerance conflicts happen when dependent features are cut in different setups and the chain can’t preserve a common datum. The issue is rarely feature complexity — it’s that alignment must survive fixture resets, material stress, and finishing.

For example, a bore and keyed interface may both be simple operations. But if the key is cut after finishing without restoring the original datum, runout becomes a guess instead of a controlled outcome. Same with intersecting pockets: each looks fine in isolation, but wall stiffness shifts during machining break the alignment the tolerance chain is built on.

What to do before quoting

Ask:

“Where does the datum get re-established as these related features move downstream?”

If the supplier cannot describe this op-by-op control, you’re heading toward a quote that explodes later — or a quiet rejection.

When do GD&T datums create unholdable CNC tolerance loops?

GD&T datums become unholdable when the datum feature changes shape or position during machining or finishing, and the supplier cannot re-establish the reference before downstream operations. The loop breaks quietly, even though the drawing logic remains sound.

Here’s how it usually happens:

Op-10 sets a perfect primary datum — solid, stable, measurable.

Op-20 adds stress, tool pressure, or vibration.

Op-30 re-clamps on a surface that’s no longer the same datum.

Then anodizing adds a few microns of uneven growth.

The final inspection reveals a “mystery” shift… but it wasn’t mysterious at all — the datum walked away from the tolerance chain mid-process.

Shops reject these designs not because the callouts are wrong, but because they can’t verify the same reference again once the part starts to move. And if they can’t verify it, they won’t own the risk.

Before quoting, ask:

“When — and on which operations — do you re-verify Datum A?”

If the first re-verification isn’t until final CMM, the result is already out of tolerance — you just haven’t been told yet.

Fix machining risks early

Why do thin-wall CNC parts magnify stack-up errors?

Thin-wall features magnify stack-up errors because the material flexes during machining and finishing, causing geometric drift at every step of the tolerance chain. Small shifts become large consequences downstream.

The drawing shows a rigid profile.

The reality?

The part behaves like a spring under load — and every cut changes the spring.

Depending on the design, here’s what amplifies error:

- Clamp pressure that distorts geometry before the cut

- Tool deflection that leaves features “near” spec but not stable

- Residual stress pushing walls out after roughing

- Anodizing adding material unevenly on flexible sections

General suppliers only see the tolerance drift after production, not during. By then, you’re in delay mode — and someone’s arguing who pays for scrap.

Before quoting, ask:

“What supports or mid-process checks will you use to keep these walls stable while cutting the rest of the chain?”

If the shop treats thin-walls like normal parts, the tolerance will shift more than the entire allowed stack.

Thin walls don’t just add complexity —

they expose the difference between a capable supplier and a hopeful one.

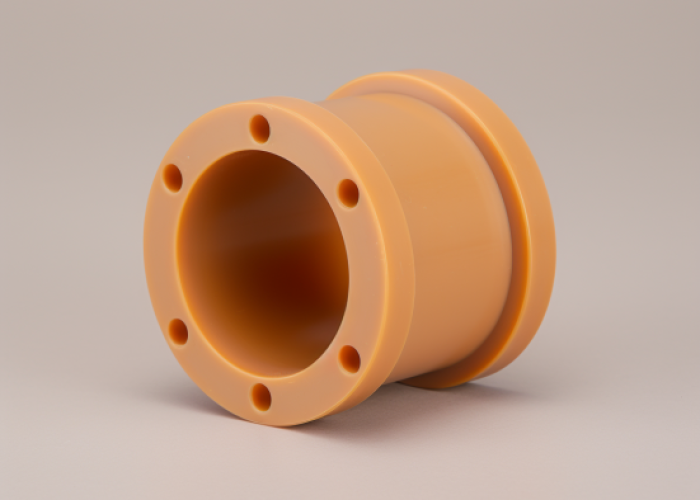

Which CNC dimensions shift after anodizing or heat-treat?

Any tolerance-chain dimension that changes with coating thickness or heat-treat distortion becomes unstable unless the supplier compensates for it ahead of time. That’s why parts that pass machining inspection fail after finishing.

Machining creates stress patterns.

Anodizing or heat treat redistributes those stresses.

Flat surfaces turn slightly convex.

Bores shrink — and not evenly.

Alignment that was perfect becomes a few hundredths off.

The painful part?

Most general job shops only measure before finishing — when it’s still the wrong geometry.

As a result:

- Bore-fit features become interference

- Parallelism shifts unpredictably

- Concentricity fails functional meshes late

- CMM findings arrive too late to recover timeline

You can spot this supplier weakness early.

Ask them:

“Which features will you verify again after finish, and how will the pre-finish passes be compensated?”

If they can’t give a two-step inspection strategy —

you’re staring at late-stage rejects and emergency rework.

Finishing isn’t cosmetic.

In tight tolerance chains?

It’s the moment reality shows up.

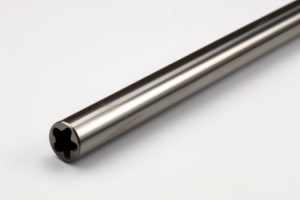

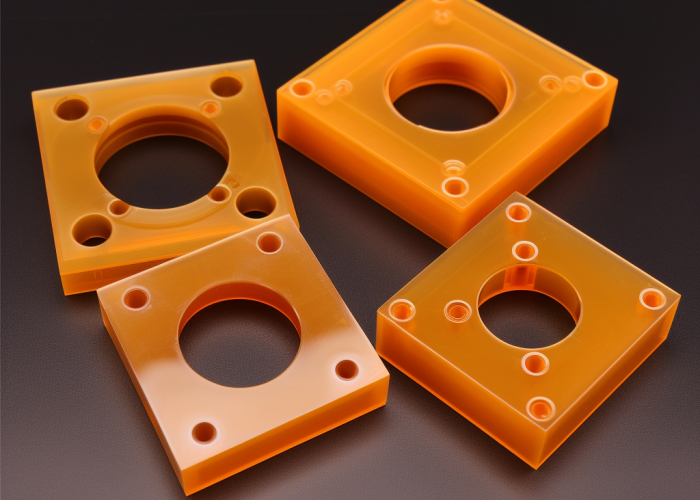

Are your CNC alignment fits and material stability compatible?

Alignment stack-ups fail when the material expands, contracts, or relaxes differently than the fit relationship assumes — even if every feature measures correctly in isolation. A perfect bore-to-boss alignment on the machine can turn into a misfit during assembly because the material changed shape after cutting or finishing.

Aluminum is the usual culprit — pockets relieve stress, walls relax, and alignment moves without warning. Titanium springs back aggressively after tool pressure. Plastics change shape with temperature shifts between ops. The drawing assumes a static world. The machine lives in a dynamic one.

Subtle mini-case:

A 6061 housing maintained 0.02 mm concentricity during machining — then shifted to 0.06 mm after roughing opened internal cavities.

Before sending RFQs, ask:

“Which features require stability checks after roughing — not just at the end?”

Strong machining partners will point to where the part moves and when to trap that movement. Struggling ones won’t mention stability until you’re already late.

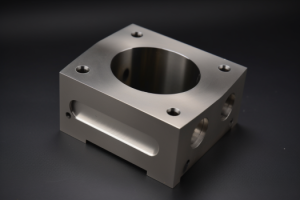

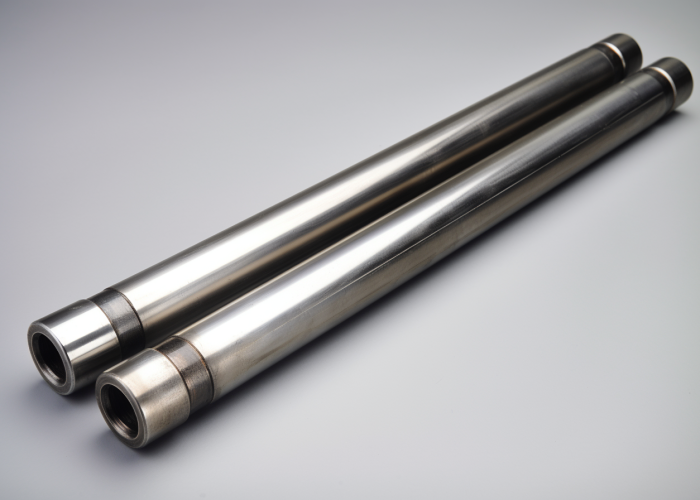

Which CNC tolerance chains require multi-op fixturing suppliers can’t control?

Tolerance chains that rely on re-clamping multiple times will fail if the supplier cannot preserve the same datums in every setup. Each new fixture position introduces a small error — those errors add up faster than the tolerance budget.

If a shop must clamp on a non-fiducial surface just to hold the part, the tolerance chain is already compromised. If the datum feature becomes inaccessible mid-process, alignment becomes hope instead of control.

Mini-case (tight, measurable):

A milled + bored enclosure failed 80% of concentricity checks when the supplier changed fixturing in Op-3 — but passed 100% when datums were re-established at each op.

Ask early:

“How many times will this part move fixtures, and how is the primary datum restored each time?”

A good answer shows a plan.

A vague answer shows a future no-quote.

How do hidden CNC surfaces cause CMM failures in tolerance stack-ups?

Hidden functional surfaces cause tolerance-chain failures when they can’t be inspected until every step is complete — leaving no feedback loop earlier in the process. The supplier only discovers the broken alignment after the coating is done, ports are opened, or access holes are machined.

It’s not uncommon:

alignment that looked fine from the outside becomes unusable the moment the CMM finally sees the internal geometry.

Mini-case (zero fluff):

An internal alignment requirement missed spec by 0.04 mm after black anodizing — because the first measurable access occurred after finishing.

Quick sourcing test:

“When is the first moment you can probe the surfaces that control the function?”

If the answer is end-of-line only, you’re buying risk disguised as confidence.

Great machinists don’t just cut metal —

they engineer when measurement happens, so failure shows up early enough to fix.

Which CNC stacked tolerances make your quote cost explode?

Stacked tolerances explode costs when the supplier must guarantee relationships they can’t control until the entire build is complete. The more dependencies in the drawing, the more risk the supplier must financially absorb. And when the supplier doesn’t have visibility into that risk until the final operations, they add pricing padding — sometimes doubling the quote — to protect themselves from late scrap.

Engineers often assume price comes from complexity of individual features. In reality, price comes from the fear of hidden failure. When ten surfaces all depend on one another after anodizing, blasting, and re-clamping, a shop must assume everything could drift at any point. The smart ones raise the price; the desperate ones quote low and hope nothing goes wrong until the PO is signed.

A quick sourcing move is simply asking the fabricator which dimensions they need to confirm earliest to protect the tolerance chain. If they cannot point to a specific relationship and a specific operation, they are guessing. And guessing is expensive.

Which CNC orientation or concentricity stack-ups aren’t manufacturable?

Orientation or concentricity stack-ups become unmanufacturable when the referencing logic works only on a static print — not on a dynamic part that shifts during production. The part changes shape as it is cut, clamped, and coated. If your tolerance depends on a feature that is transformed after its reference has already been used, the chain becomes impossible to hold, no matter who machines it.

Experienced machinists don’t say, “We can’t make this.” They say, “We can’t make this in this order.” The fix isn’t always design change — sometimes the right sequencing avoids a tolerance trap entirely. But if the supplier never brings up the sequence, that’s a sign they don’t fully grasp what the tolerance relationships demand.

So instead of asking, “Can you hold this?” ask, “Which feature needs to be last so orientation doesn’t walk away from us?” A real professional will know immediately. Others will stare at the print and hope.

How do you detect a CNC supplier struggling with your tolerance chain?

A struggling supplier talks about the print more than the process. They ask generic questions, push for tolerance relaxation early, and focus solely on final inspection rather than the checkpoints that prevent drift in the first place. Silence and vague updates are another sign — not because they’re hiding something, but because they don’t yet understand what’s going wrong.

You’ll know confidence when you hear it. A capable supplier quickly points to where tolerance could break and how they’ll keep that from happening. They describe inspection in the middle of production, not at the end. They don’t try to renegotiate tolerances until they’ve shown you the exact cause of movement.

A quick sourcing check: ask them to explain the flow of tolerance protection, not tolerance measurement. If all they show you is the CMM report — they’re already too late.

How do you confirm CNC tolerance feasibility before your lead time explodes?

You confirm feasibility by making the supplier simulate tolerance control before quoting — not after production. You don’t need lengthy reports or expensive FAIs. You simply need the machinist to explain the sequence of machine setups, how the datum is restored between them, and when the functional surfaces are first validated.

The shops that do this well never get defensive. They walk you through how they’ll trap drift early. They show you where the finishing step will be compensated into machining. And they demonstrate how failure would be discovered when there is still time to prevent it, rather than after a box of scrap parts arrives.

When a supplier can clearly articulate how they’ll hold your tolerance chain — operations, inspection timing, stress-relief strategy, finishing allowance — you’ve already protected your schedule. When they can’t, delays are inevitable; they just haven’t happened yet.

Conclusion

When tolerance stack-ups fail, it’s rarely the design — it’s the supplier’s process. Confirm how your machining partner maintains datum control, prevents drift, and verifies alignment during production. That’s how you protect your deadline without compromising function or tolerance.

Frequently Asked Questions

Because tolerance control isn’t validated before quoting. Final inspection reveals failure too late to recover schedule.

Only if function allows. First verify whether process sequencing and in-process QC can protect current specs.

Often yes. Operation sequence and fixture strategy changes can recover alignment without altering geometry.

Clear datum hierarchy, finish notes, and functional tolerance priorities — enabling suppliers to engineer control, not assumptions.

Before any closure or finish operation that blocks probing. Early access prevents late surprises.

Ask when the primary datum is re-verified. “Final inspection only” means capability won’t match requirement.