Your coating finish failed — peeling, discoloration, blocked threads, or post-coat dimensions out of tolerance. When this happens, suppliers often blame “finish risk” or material choice, leaving you uncertain where the failure actually came from.

Most coating failures are caused by supplier process control breakdowns, not material or design flaws. If prep, masking, fixturing, bath control, or post-coat inspection weren’t tightly controlled, failure is predictable — not unavoidable.

Below, you’ll learn how to isolate the exact failure point, identify supplier responsibility with evidence, and decide whether rework, remake, or switching suppliers is the lowest-risk path before delivery is impacted.

Table of Contents

Did material choice or supplier prep cause the coating failure?

If coating adhesion failed, assume supplier prep failure unless material incompatibility was documented before coating.

Material choice almost never causes spontaneous coating failure. When peeling, blistering, or flaking occurs, the default cause is missing or incorrect surface preparation—not the base alloy.

Here’s the decision point suppliers avoid: Was the prep sequence defined, recorded, and verified before coating began?

If degreasing, etching, activation, or surface conditioning was skipped, shortened, or mismatched to the coating chemistry, adhesion failure is expected. When suppliers blame “material risk” after parts fail, it usually means prep responsibility was never locked down.

This matters because re-coating without correcting prep will almost always fail again. If the supplier cannot show which prep steps were applied—and why they were correct for that material—there is no technical basis to approve rework.

Decision rule:

- No documented prep plan before coating → do not approve recoat

- Material blamed only after failure → treat as supplier process fault

Before authorizing rework or remake, confirming whether prep—not material—caused the failure prevents repeating the same loss. That confirmation can usually be made from drawings, finish specs, and failure photos—without running another risky batch.

Do inspection results point to bad surface prep or wrong coating chemistry?

Inspection patterns tell you whether the failure is recoverable—or guaranteed to repeat.

The key is whether defects are localized or systemic.

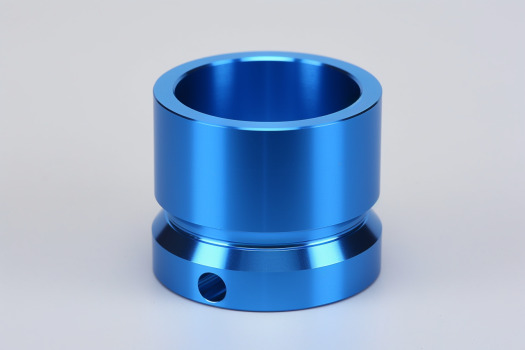

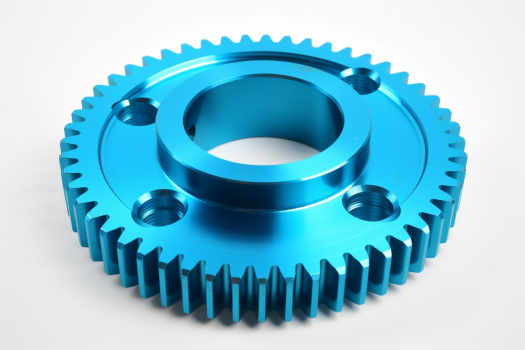

Localized failures—peeling at edges, around holes, or near masked features—almost always indicate surface prep breakdown. Systemic failures—uniform discoloration, brittleness, or thickness drift across all parts—point to incorrect coating chemistry, bath control, or cure parameters. When suppliers collapse both into “finish risk,” accountability disappears.

Here’s the decision point that matters: Do inspection results correlate with specific features or appear everywhere?

If the pattern is repeatable and consistent, the root cause is identifiable. Recoating without changing the underlying process (prep or chemistry) is not corrective action—it’s repetition.

Decision rule:

- Localized defects → prep failure, recoat only after prep correction

- Systemic defects → chemistry/process failure, remake likely required

If your supplier can’t explain why the inspection pattern looks the way it does—or can’t tie it back to a controlled process step—you’re being asked to approve rework without evidence. That’s how coating failures repeat.

Was uneven coating caused by poor fixturing or outsourced process gaps?

Uneven coating almost never happens randomly — it’s usually caused by uncontrolled part orientation or fragmented process ownership.

Thickness buildup on one face, thin edges, or inconsistent coverage across identical parts usually points to how parts were held, spaced, or transferred between vendors.

This failure often appears when machining and coating are handled by different parties without a locked handoff. Fixturing decisions get made at the coating stage, not the design or machining stage, and no one verifies whether part orientation will trap solution, shadow critical faces, or overload edges. When that happens, coating thickness becomes a guess instead of a controlled outcome.

The critical question isn’t whether the coating “meets spec.” It’s whether the same fixturing and orientation can be reproduced again. If the supplier can’t show how parts were racked, spaced, and grounded—or if coating was outsourced with no fixturing documentation—approving rework just repeats the same uncertainty.

At that point, uneven coating isn’t a quality defect. It’s a process gap.

Before accepting recoat or remake, it’s worth confirming whether fixturing control exists at all. If it doesn’t, repeating the process rarely improves the result.

Coating Failed? Get a Second Opinion

Upload failed part photos and inspection results. We’ll identify the real cause fast.

Are damaged threads or holes a design issue — or a supplier masking failure?

When threads or holes are damaged after coating, the failure is almost always masking-related — not a design flaw.

Threads don’t “fail” because of coating. They fail because masking was incomplete, inconsistent, or removed incorrectly.

Suppliers often suggest thread damage means the design should have looser tolerances or different thread classes. That explanation only holds if masking strategy was reviewed and approved before coating. In reality, thread failures usually come from rushed masking, soft plugs used where rigid caps were required, or post-coat chasing used to “fix” blocked threads.

Here’s the accountability check suppliers struggle with: Which features were masked, how were they masked, and was masking verified before coating began?

If that answer is vague, the damage didn’t come from the drawing. It came from uncontrolled handling.

Once threads are damaged, rework options shrink quickly. Chasing removes coating protection. Oversizing compromises fit. Recoating often worsens the problem. That’s why approving rework without understanding masking failure often locks in permanent risk.

If threads or holes matter functionally, confirming masking control before approving corrective action prevents a cosmetic issue from becoming a mechanical one.

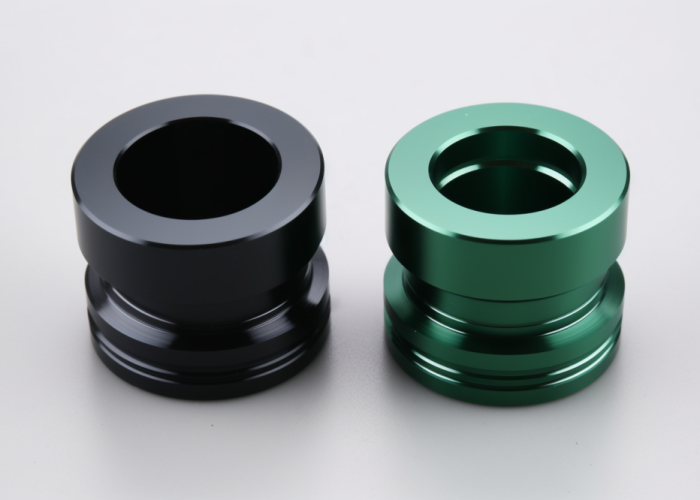

Did color mismatch occur due to bath contamination or uncontrolled curing?

Color mismatch across parts usually indicates bath condition drift or inconsistent curing — not subjective color variation.

When color shifts between lots, between faces, or across parts in the same batch, the cause is almost always process instability.

Bath contamination shows up as inconsistent hue or saturation. Cure instability shows up as parts that darken, fade, or shift after handling or assembly. When suppliers explain this as “normal finish variation,” they’re often avoiding a harder question: Was bath chemistry monitored and cure parameters controlled for this run?

Color issues become critical when they affect brand appearance, assembly matching, or customer acceptance. Recoating without stabilizing bath condition or cure timing rarely fixes this. It often amplifies variation, especially when old and new parts are mixed.

The practical decision hinge is simple: If the supplier can’t show recorded bath condition and cure parameters for the failed batch, there’s no evidence the result can be reproduced correctly.

At that point, accepting rework becomes a gamble, not a corrective action.

Before approving any remake or recoat, verifying whether color control exists at the process level avoids chasing appearance issues across multiple builds.

Can post-coating dimension failures be recovered within tolerance?

Post-coating dimensional failure is only recoverable if the coating allowance was engineered before finishing.

Once coated parts measure out of tolerance, recovery depends entirely on whether thickness buildup was anticipated and controlled upstream.

If coating allowance was never defined, post-coat dimensions drifting is not a surprise — it’s a predictable outcome. Grinding, chasing, or selective removal may temporarily “fix” fit, but it also removes corrosion protection and introduces variability that’s rarely documented or repeatable.

The key escalation point is this: Was coating thickness modeled into the tolerance stack before coating began?

If not, any recovery attempt is improvisation. And improvisation transfers risk directly to assembly, performance, and inspection approval.

At this stage, approving rework without a documented allowance strategy doesn’t solve the problem — it just delays the remake decision while compounding cost.

Should failed coating be recoated or parts remade?

Recoating only works when the root cause has been corrected — otherwise, remaking is the lower-risk option.

Suppliers often push recoating because it looks cheaper and faster. In reality, recoating without a verified process correction has one of the highest repeat-failure rates in finishing.

Recoating carries hidden risks: trapped contamination, altered surface condition, cumulative thickness buildup, and reduced adhesion strength. If the first failure came from prep, fixturing, masking, or bath instability, recoating repeats those same variables — often with worse outcomes.

Here’s the decision hinge most teams miss: Can the supplier show what changed between the failed run and the proposed rework?

If the answer is vague — “we’ll be more careful” or “we’ll adjust the process” — there’s no technical justification to approve recoat.

At this point, approving recoating doesn’t reduce risk. It postpones the remake decision while consuming schedule and budget.

What evidence proves your supplier’s coating process caused the failure?

If the supplier can’t produce process evidence, the failure should be treated as their responsibility.

Coating failures are only debatable when data exists. Without it, accountability is already decided.

Process evidence isn’t complicated, but it is specific: prep sequence records, masking definition, fixturing method, bath condition logs, cure parameters, and post-coat inspection data. When suppliers lack this documentation, it’s usually because the process was never controlled tightly enough to record.

This is where escalation becomes unavoidable. If the supplier cannot explain the failure using their own process data, there is no basis to trust the next run.

At that point, the issue is no longer the coating — it’s supplier capability.

Continuing with the same supplier without evidence doesn’t just risk repeat failure. It removes your leverage when the next defect appears.

Which process control did your supplier fail when claiming “finish risk”?

When a supplier cites “finish risk” without naming a specific failed control, the root issue is almost always missing process control.

Valid coating risks can be traced to defined variables such as surface preparation, bath condition, fixturing orientation, curing temperature, or dwell time. When none of these are identified, the explanation is not technical—it’s evasive.

This matters because a failure without a named control point cannot be corrected. If the supplier cannot say what failed, there is nothing concrete to fix. Rework or remake decisions made under that uncertainty are guesses, not corrective actions.

At this stage, the coating itself is no longer the main concern. The inability to identify a failed control signals a breakdown in process ownership. Once that happens, confidence in any proposed fix should drop sharply—because control, not intent, determines repeatability.

Can your supplier reproduce the finish correctly on a remake?

A remake only reduces risk if the supplier can reproduce the coating process, not just remachine the part.

Without documented prep steps, locked fixturing, monitored bath parameters, and defined curing conditions, a remake carries the same failure risk as the original run.

This is where many teams lose leverage. A remake feels decisive, but if the supplier cannot explain exactly what will be different—and how that difference will be verified—the second run has no stronger foundation than the first. Any deviation then becomes “normal variation,” making rejection harder rather than easier.

If the failure mechanism was never identified, a remake does not reset risk. It carries uncertainty forward while consuming more schedule and budget. At that point, repeating the same supplier process is not a correction—it’s a rerun.

Recoat, Remake, or Switch?

Send your drawing and failure details. Get a clear recovery path.

What are the fastest replacement options when coating failure delays delivery?

The fastest recovery from coating failure comes from securing parallel replacement capacity, not waiting on rework or remake cycles.

Once reproducibility is in doubt, time is lost debating fixes that may not work.

Teams that recover fastest stop tying delivery to a single uncertain process. They protect schedules by confirming alternate capacity, validating finish capability elsewhere, and keeping options open—even if the original supplier continues working in parallel.

At this stage, speed no longer comes from optimism. It comes from redundancy. Waiting for one more attempt often costs more time than starting a clean replacement path early. When coating failure threatens delivery, protecting the timeline becomes the priority—not proving who was right.

Does coating failure justify switching suppliers instead of rework?

Switching suppliers becomes the safest option when coating failures reveal a lack of process control, evidence, or reproducibility.

Rework is only reasonable when the supplier can clearly identify the failure mechanism and demonstrate how it has been corrected. When those conditions aren’t met, continuing with the same supplier shifts risk—not reduces it.

By this point, the pattern matters more than the defect. If explanations stay vague, controls aren’t documented, and outcomes can’t be reproduced, the issue is no longer a single coating failure. It’s a capability mismatch. Accepting rework under those conditions often locks teams into repeated delays, compounding cost, and shrinking leverage.

Switching suppliers in this situation isn’t reactive. It’s preventative. Teams that move early protect delivery, restore decision control, and avoid becoming dependent on promises instead of proof.

When coating failure exposes process gaps rather than isolated mistakes, changing suppliers is not escalation—it’s professional risk management.

Conclusion

Coating failures signal missing process control, not bad luck. When rework lacks evidence and repeatability can’t be proven, risk shifts to you. Before approving rework or remake, submit your drawing and failure details for a fast second opinion to confirm the safest next step.

Frequently Asked Questions

Recoating is only safe if the supplier can clearly explain what caused the failure and what process step has been corrected. If no specific change is documented, recoating usually repeats the same failure and increases scrap, delay, and inspection risk.

A remake is safer only when the supplier can reproduce the full coating process with controlled variables. If fixturing, prep, bath condition, or cure parameters were not defined previously, a remake does not reduce risk—it carries the same uncertainty forward.

Ask for process evidence, not promises: prep sequence records, masking method, fixturing orientation, bath condition logs, curing parameters, and post-coat inspection data. If the supplier cannot provide these, there is no technical basis to trust the next run.

Switching is justified when failures reveal vague explanations, missing process control, or inability to reproduce results. At that point, continuing is no longer corrective—it’s risky. Changing suppliers becomes a professional risk-management decision, not escalation.

If the supplier cannot show documented surface prep, masking, fixturing, and curing parameters from before coating, the failure is almost always process-related. Design issues are identifiable in advance; undocumented failures discovered after coating point to missing control, not drawing flaws.

The fastest protection comes from securing a parallel replacement path while decisions are still open. Waiting for rework approval often costs more time than validating an alternate supplier early—even if the original supplier continues working.